Hmmm....as a Prof own words..mana ada !! ujud !

As all rank and file,I wonder about our dear children's future.The Prof.do have some words of advise here.

Which direction?

How?

Why?

As my mum's complaining about my son level of English?

I must say hers is better than his.I quite agree with her remark.

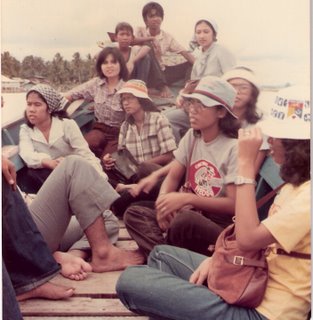

As per conflict of identity.Ages ago the fear of missionary school by my fellow country man sparks a bit of controversial.Negative comment been thrown at to parent whom sent their children to English school during the Malaya day.

The fear was basically due to the low esteem and passion for education by my fellow country man as compared to other races.

As a result when we pick up,they already went up!

I went to a Catholic Kidergarten when I was 5 years of age,but it does not a bit fades away my believed in Allah Al Mighty.

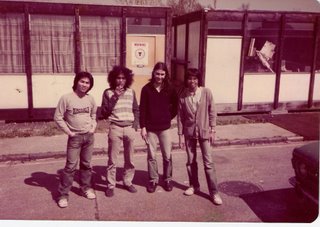

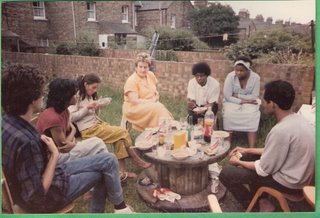

Even my Kak Long, when she got a scholarship to do Engineering in the UK in early 1970's,yes that was the 'Golden Generation'and according to sources some even commented her absence from Malaysia would either end her up either with an European hubby or she would abandoned her own religion.It does not happen at all.

My oh my .....such a shallow thinker.

Probably the wisdom of Assoc.Prof Azmi do specks by it self.Its a refelection of the worries and the vision and hope of a every man on top of 'Clapham Ommini Bus'.

Do read it its thought provoking.

xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx

Republish with permission from the Prof.himself.

His concerned by any 'other Beast of Burden'sholdered responsibility.

I feel your concerned Prof.

xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx

Presented at:

The Star/Asian Centre for Media Studies Conference 2006

Kuala Lumpur

18 – 19 August 2006

Dr. Azmi Sharom

Associate Professor

Faculty of Law

University of Malaya

This paper shall begin with a disclaimer. I do not, in any way pretend to be an expert in Higher Education Theory. Neither am I a holder of any high management posts either in my university or the government, which would have put me in the forefront of higher education policy making. This paper therefore is about the view from the bottom. It is the opinion of an ordinary lecturer based on the experience of working in a Malaysian public university for the past sixteen years.

The question here is can Malaysian universities attain and maintain world class university standards? This begs the preliminary question: what is this “world class university standard”? It is submitted that such a university would have to have the following qualities:

a. Graduates who are employable and who are desired by employers, not just domestically but internationally.

b. Academic staffs that are recognised world wide as authorities in their fields. This is achieved through the publication of research findings in international forums; be they internationally subscribed refereed journals, books published by reputable publishers and international conferences.

c. An academic programme that attracts students from all over the world

d. An academic atmosphere that attracts staff from all around the world

However, I am uncomfortable with the term “world class” simply because it is the type of term that Public Relations people and politicians love to bandy about. It is the type of term that could easily lead to empty sloganeering. It appears obvious that the qualities mentioned above are what make a university good; full stop. But then having a poster saying “Our University is good” does not make for a particularly enticing poster.

What shall be discussed here then is whether Malaysian universities have the elements needed for them to be recognisably good universities, what are the problems or obstacles which could get in the way of that ambition and what can be done to overcome them.

How Good Are We?

It would be tempting at this juncture to refer to some ranking or the other to determine how good Malaysian universities are. I shall not succumb to that temptation for the simple reason that I believe rankings to be a dubious exercise and to celebrate or commiserate over them is folly. This is because depending on the differing criteria and values put in place by the organisation doing the ranking, one’s results can be very different. And, as we have learnt in the University of Malaya to our great embarrassment, sometimes glaring mistakes are made. Such as when we were mistakenly ranked in the top 100 of the Times Higher Education Supplement because the rankers did not know that in Malaysia students are classified by ethnicity and so when a student is classified Chinese, it does not mean he is from China; hence the number of “foreign” students were unnaturally high.

Therefore, using the absolutely non-empirical method of listening to the people, it is submitted that Malaysian universities face something of a confidence problem. That is to say, there is a lack of confidence amongst the Malaysian people about how good we are. To a certain extent this is reflected in the high number of unemployed graduates that we have. The numbers vary depending on who you listen to but it is at least 50000 of them. This does not include the number of under employed graduates, those in employment but doing work that does not need the paper qualification they have.

From the point of view of a UM law lecturer, although our students are all employed almost as soon as they graduate, there is the usual bemoaning of their standards. What is telling is that their knowledge of the law and their ability to do research is by and large accepted as being fair to good; however, the usual complaint is the lack of confidence and the poor communication skills. And by communication skills, it is meant mastery of the English language. It would appear therefore that at least for our young lawyers, it is the intangible “soft skills” that is lacking.

With regard to academic staff in general, it would be unfair to say that we do not have members who are recognised the world over. There are many throughout the University of Malaya, and I am certain surely in the other public universities as well, who are given due recognition by being head hunted by international organisations; through collaborations with highly reputable institutions at home and abroad; invitations to present findings and opinions at international forums and journal citations. But the numbers are not very large and more can be done to attract the bright and the able to not only join the institutions but to stay.

Malaysian universities do not have a very large population of foreign students, but there are some, especially at the post graduate level. There is also a fairly small number of expatriate staff (with the exception of The International Islamic University Malaysia). The issue here is if we were to try to attract more students and staff from other countries, what would be the objective and bearing that in mind, how should it be done?

It would be fair to say that Malaysian universities are really not in the big leagues, with regard to our recognition amongst academics world wide. But perhaps more importantly we are not seen in a favourable light amongst the people of this country. So, to answer the question “how good are we?” the answer would probably be “not very”.

Student Quality

It has been a popular opinion in Malaysia that foreign graduates are somehow better than local graduates. Assuming this is true, it would put to test the argument that the reason our local graduates are so poor is simply because our primary and secondary schooling system has failed them. The argument goes along the lines of not having certain basic skills like public speaking and critical thinking properly infused into them at a young age, they come to higher education ill equipped and the universities are then burdened with having to be remedial centres.

This is not to deny that much can be done at the primary and secondary school level to move away from rote learning and memorizing, but if all our woes are to be placed on the early and mid level education of our young people, how then does one explain the supposed higher quality of those who graduated from abroad. After all, they have by and large shared the same primary and secondary experience as their counterparts in Malaysian universities.

Perhaps things have changed since when I was in a student in England, but I never once had to attend a soft skill class. I doubt many if any of my generation educated there had to either. Furthermore, having studied in three British universities and having worked for so long in a Malaysian university, at least in the Faculty of Law, I can see little difference in what goes on inside the classroom. Where then is the difference?

It is suggested that the difference is in the university experience as a whole. A university life which exposes a student to different experiences and opinions, along with one where they are empowered to govern themselves and their lives, would lead to a more mature and worldly graduate. Such experiences are sadly lacking in local campuses.

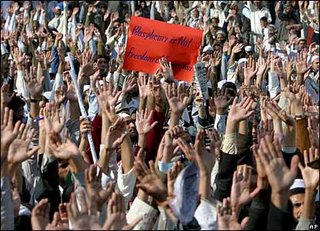

If there is one word that can be used to describe campus life in Malaysia, it is “stifling”. It would be easy to blame the woes on the Universities and University Colleges Act, but one has to be more specific than that. Looking at the parent Act itself, the only real limitation placed on students is the restriction from joining political parties and to show open support for any of these parties. This by itself is a blatant breach of the constitutional rights of students, but it is nothing compared to the regulations made under the authority of the Act by universities themselves.

Students do not have a Union; instead they have a fairly toothless Student Council which acts as a middle man between the student body and the university. It has none of the powers that a Union would have, such as the power to strike. The elections of this seemingly harmless Council have been plagued with accusations of vote tampering, and blatant biases shown by university authorities for one group of students over another; what has been conveniently labelled as Pro-aspiration (read government) and anti-establishment groups. These accusations have yet to be properly investigated by an impartial third party.

But it is the day to day running of student activities that see such a tight rein being placed on campus life. Everything, even the most banal activity needs the approval of the Student Affairs Department. If putting up posters to celebrate the lantern festival needs a Student Affairs stamp of approval, what then the joining of NGOs or the organisation of talks, or even the ownership of books deemed pro opposition. To say that our students are fettered is an understatement of the saddest kind.

What then needs to be done? Ideally, the University and University Colleges Act should be repealed altogether, at least the parts which do away with the constitutional rights of students. However, realistically, this is unlikely to happen. The ball then is firmly in the court of the university authorities themselves and it is for us to look at they way things are run and to ask ourselves truthfully what this sort of governance is doing to the quality of our graduates.

The following can be done if there is a will to do so:

- Review all university regulations with regard to students with the ultimate aim of providing for student autonomy

- Ensure that the Student Affairs Department is a totally non political body whose ambit is purely the welfare of students

- Allow for independent self governance

- Place the absolute minimal restrictions on the freedom of association, expression and assembly

The paternalistic way our campuses are run at the moment has the effect of producing meek, inexperienced and timid graduates. It also has the further effect of making our universities completely unattractive to students from abroad, unless of course they live in totalitarian dictatorships.

Another issue which is rather sensitive is the matter of meritocracy. It has been the policy of the Government to have a merit based system of intake. With the exception of UiTM, all public universities are practicing this. It has been rightly pointed out however that there are two main avenues to a university education. One is to sit for the sixth form exam which takes two years (open to all) and the other is to do the Matriculation Programme which usually lasts a year (open primarily to Bumiputra fifth form leavers). The question is therefore, how can the system be based on meritocracy when the two avenues are not merit based? Furthermore there are questions as to how comparable are these two programmes in the first place.

These are valid concerns. The entire idea of having a merit based system of entry is to ensure that only the best students enter university and also to ensure a degree of fairness. However, if there is a perceived need for affirmative action, then things can get complicated.

It is submitted that if there is going to be affirmative action, then let there be affirmative action. But, let it be done openly. Calling a system a merit based system, but in fact setting it up in such a way as to be affirmative action through the back door is ultimately going to do more harm than good.

Whatever the ultimate aim is, be it a true merit system or one with affirmative action incorporated, a single avenue for university entry is the only way that the applicant’s true ability can be gauged; this along with perhaps further aptitude testing to be done by the individual faculties. Testing which can be openly assessed by independent, preferably international bodies.

In a true meritocracy, a single avenue system will mean greater fairness. In a system with affirmative action, it would mean that it is easier to judge the minimum standard required for an applicant to be able to withstand the academic rigours of a chosen course. For example, one may wish to set a quota for a particular group. That quota however can only be filled by those who actually obtain a minimum grade. If not enough achieve that grade, then the extra spaces should be open to competition.

Let me state here that personally, I think at this point in our development a university entry system has to be based on merit and merit alone. But my point here is that even if the official policy is otherwise, let us please call a spade a spade and make sure that affirmative action does not damage the quality of the university because a class populated with students of vastly differing abilities is a class impossible to be taught well.

Lest it is forgotten, universities have to ensure that what does happen in the classroom is of the highest standard, based on academic vigour (we must not be afraid of failing students) is relevant and current. Things like reading lists with a majority of books older than the students should be a thing of the past (with the exception of courses such as Shakespearean literature). In this the private sectors too have a role to play. Feedback from the private sector, at least in my experience has been of the generic sort. It is absolutely pointless to the lecturer to be told that his course is not relevant if some sort of idea as to what relevance means is not provided.

Lecturers must not take the easy way out by spoon feeding students. And if they ask to be spoon fed, as I am led to believe does occur, then it is the duty of the lecturer to ignore such calls. After all one comes to university to be intellectually challenged and if some are misguided enough to think that it is merely a certificate which is on offer, then they must be shown the error of their ways. To conclude, students must be treated as adults if we want mature graduates. They must be empowered with responsibility of self within and outside the classrooms.

Staff Quality

The pay is not the main attraction for people wishing an academic career. This is perhaps more true here than many other places. Now, with many faculties demanding at least a PhD before a person can be a lecturer, it makes it even harder to attract capable people; particularly in professional faculties.

It is of vital importance therefore that job satisfaction has to be high. In order to achieve this there are two things that a university must do. Firstly provide the sort of atmosphere where good teaching and research is encouraged. Secondly to properly reward those who strive towards and achieve academic excellence.

The matter of an academic atmosphere is one which has to do with attitude more than anything else. It needs a fundamental belief in academic freedom, integrity and autonomy. Academics must be free to explore fields of research and to express that research in their teaching and writing without fear or favour, secure only in the knowledge that as long as the work is of rigorous academic quality it would be treated as such.

There are of course practical ways to make this process less burdensome. Easy and generous access to funding is perpetually on the wish list, but seeing as how money is never easy to come by, perhaps what is more important is the knowledge that the university is sparing what it can for research and that resources are directed towards such ends as opposed to being squandered on unnecessary frivolities. Another boon would be the lessening of red tape for applications for such funds as well as for activities such as organising and presenting at conferences.

Reward comes in the form of recognition and this takes the form of promotions. As such it is important that promotions are given based on academic merit (i.e. excellent research and competent teaching) and nothing else. To take into consideration matters outside academic work not only means having poor Professors, but also would encourage unhealthy practices. For example, if being Dean is more important than having papers published, the post would be seen as a legitimate avenue to promotion and would become highly politicised.

A sound promotion exercise should be a transparent one. The method is simple. Publish the curricuilum vitae of those who are promoted. Let the campus community scrutinise them in order to see if they truly merit such an honour. In fact, the curriculum vitae should be published before confirmation of promotion to ensure that there can be no doubt a person’s accomplishment is true. If things are open to scrutiny, then irregularities can be seen and honesty becomes best practice.

We have also reached a stage where attracting sound academics should be of primary concern. This means there can no longer be race based appointments and promotions. The pool of talent is not so large that such societal gerrymandering can be tolerated any more. This goes for the appointment to leadership posts as well. If any of the above ambitions with regard to staff and students is to be achieved then the appointment of leaders is essential. A Vice Chancellor who is an academic, a diplomat, an administrator and someone who understands what academic values are, is invaluable in setting the tone of an institution.

Like the students, Malaysian academics too have certain laws hanging over our heads. The one that I wish to raise here is the Statutory Bodies Discipline and Surcharge Act and its off spring the “Aku Janji” or “Oath of Allegiance”. This Act basically states that a lecturer (who classifies as a statutory body employee) can not say anything for or against government policy without permission. It does not take much to see that such a provision is unworkable and is potentially abused as a blunderbuss of a deterrent against any one who may have views contrary to the government of the day. It is hardly a piece of legislation to encourage academic endeavours, especially in the social sciences and humanities.

This, on top of the laws that apply to all Malaysian citizens like the Internal Security Act, the Official Secrets Act and the Sedition Act, has created a culture of fear on campuses. A culture where it is hard to get an opinion from those who should have an opinion, whose job is to have an opinion. Instead the atmosphere on campus becomes one where the tendency is for parochialism. It is after all safer.

Research

Research needs funding and being an academic lawyer who has never had the need for large sums of money to do research, I would leave this issue to those more qualified to discuss. However, there are some developments that have to be addressed, namely the creation of new universities and the policy of increasing student numbers.

If the numbers of universities are increased without the necessary resources, in terms of money and personnel, then how can we expect any good research to be produced? Similarly if universities are burdened with huge student intakes, the staff would be unable to research because they will be too busy teaching. As such, tough decisions have to be made with regard to whether we want quality universities (which imply quality research) or merely teaching institutions.

International staff and students

The first step towards attracting international students and staff is to have small short term joint projects. Visiting professors should be encouraged, as long as the visitor has value to add to the university. Short courses with transferable credits can also be conducted in co-operation with foreign universities to expose their students and faculty to ours and vice versa.

To achieve this, the following have to be improved or changed:

- The infrastructures of universities have to be improved. By this it is meant not just the teaching facilities and the libraries, but also accommodation facilities.

- Bureaucracy has to be streamlined and efficient

- The timing of our semesters must be looked at. It is quixotic to think that universities with a semester or term system (which is what most universities are using) are going to adapt to ours. If we want to play with the big boys, we have to play by their rules, at least by their rules of timing

- English should be the medium of instruction

If we are honest, it is unlikely that students from the developed world would make a bee line for Malaysian universities for their complete undergraduate or postgraduate studies. Neither would we have large numbers of quality foreign academic staff clamouring for the chance to earn so little money. It is better as a start, to have these smaller short term type courses to inject that sort of foreign student and staff interaction rather than to try grandiose plans of attracting full time staff and students which won’t under the present circumstances work.

In the very long term however, it is of course desirable to have a healthy overseas student body. This can be done most effectively through post graduate programmes. We should therefore be looking to ensure that the standards of our programmes are high and that they match the types and the structure of programmes in top universities. Even better would be to identify niche areas where expertise can be found only here. An example would be an LLM in South East Asian law. Sound and unique courses, along with the attractions of studying in a foreign country with all the new experiences (and low costs) it entails, can be our selling point. But, it is absolutely vital that the programme must be academically very good and recognised first.

In Closing

Some good has been done in recent times. The appointments of Vice Chancellors are slightly more open than they used to be. The process needs now to be properly institutionalised and made more accountable than it is. The government has identified research universities and it is hoped that what this means is that for these universities at least there is a greater focus of purpose. Those not classified as such should now be given the kind of assistance and values to reflect their primary purpose.

But, it is submitted that looking at all the issues above, more has to be done. Political expediency must take the back seat to academic principles if our universities are to improve and improve they can. In the final analysis, it does not really matter if we are classified as “world class” or not. What matters is that we are “good” and we have a long way to go. Once we can say with confidence that we are good and it can be backed up by evidence of the four qualities mentioned in the beginning of this paper, then titles and rankings can be ignored, that is because we will be too busy being proud of our graduates’ ability and our staffs’ academic integrity, honesty and excellence.